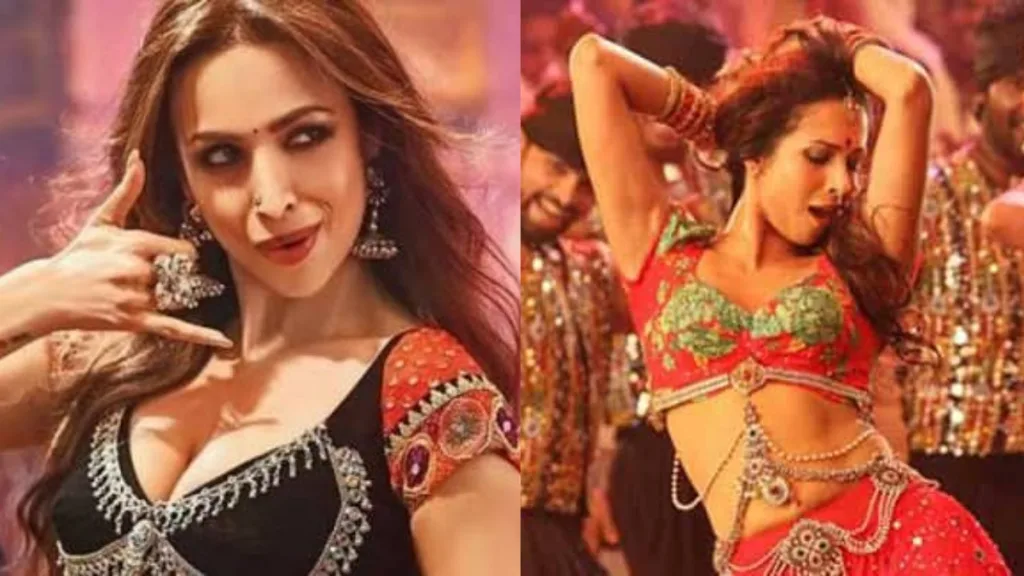

In a candid conversation about her legacy and evolving dance performances, actress and model Malaika Arora bought clarity to a topic often loaded with controversy: Bollywood item numbers. Arora, renowned for tracks like “Munni Badnaam Hui” (Dabangg, 2010) and “Chaiyya Chaiyya” (Dil Se, 1998), asserted that she has never felt objectified while performing such songs—and she emphasised that the form itself has grown in its own right.

“I have done all the songs willingly,” she told media outlets, recalling a time when such numbers were often dismissed as purely commercial hooks. “If anyone does feel objectified, then they must come forward and speak. But personally, I loved them.”

One of the most referenced moments in her career—Munni Badnaam Hui—became a nationwide phenomenon, symbolising not just a catchy track, but Arora’s unique brand of flirtatious, unstoppable energy. The song’s impact extended beyond dance floors, earning her enduring recognition.

Now, with her return in the dance number “Poison Baby” from the upcoming film Thamma (2025), Arora reflects on how the space around item songs has evolved. Speaking about the new track alongside Rashmika Mandanna, she described the process as “electric” and said, “It’s been years since I led a full-blown dance number like this in a film… I wanted the performance to feel dangerous, beautiful and untamed — all at the same time.”

Arora believes the nature of these songs has shifted significantly. What was once seen primarily as glamorous window-dressing is now more consciously crafted. In a recent interview, she pointed out: “It’s less about being provocative. Age doesn’t define your capability.”

She emphasised that the earlier stigma tied to “item numbers” is losing ground. Rather than appearing as a side attraction, these songs are now being approached as central features—opportunities for women performers to showcase strength, skill and screen presence. Arora’s career is a textbook example of this shift: from early breakout tracks like Chaiyya Chaiyya, where she danced alongside Shah Rukh Khan on a moving train, to her current status as one of Bollywood’s most sought-after dance icons.

Also Read: Emraan Hashmi Opens Up On Secular Upbringing While Defending ‘Haq’

When asked about the tagging of such songs as “item numbers”, Arora remains firm: she rejects the label, saying it’s limiting and reductive. “We shouldn’t tag them or label them as item songs,” she said. “I have never felt objectified; I knew what I was doing and accepted the context. But if someone else does feel objectified, then they must speak up.”

Her words resonate especially at a time when discussions about representation, agency and female space in Bollywood are undergoing change. Arora’s stance highlights that performance, intent, and respect matter more than reductive categorisations. She resists being boxed in by inference or branding, and instead frames her work as an active choice.

The Thamma song itself has been a talking point: fans and critics alike praised the visuals, noting that Arora and Mandanna’s chemistry and energy make the track a standout.

More broadly, Arora’s reflection invites a reassessment of how dance numbers function in Indian cinema. Are they one-dimensional spectacles? Or can they be expressions of confidence, craft and female presence? She places herself firmly in the latter camp, declaring that the legacy of these songs does not rest on controversy—but on performance, value and visibility.

As she returns to the dance floor with full force—and with the same charisma that made her a cultural touchpoint over two decades ago—Arora’s message is clear: the form may be called many things, but what matters is the performer’s clarity, consent and command.

For fans and industry watchers alike, Malaika Arora’s journey stands as a reminder that in Bollywood, a dance number is more than a hook—it can be a moment of agency.