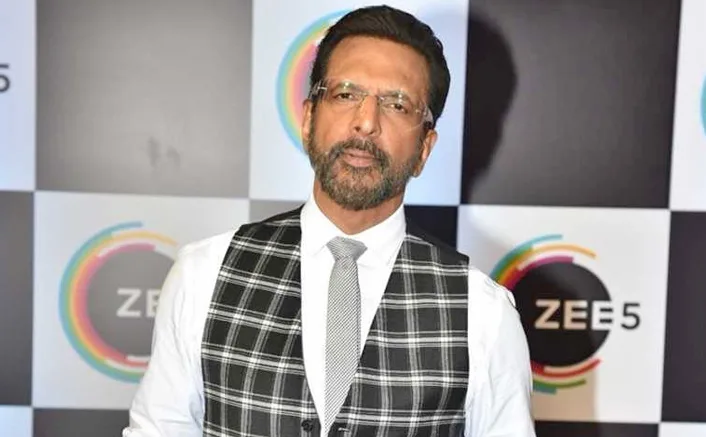

Veteran dancer and actor Jaaved Jaaferi has stirred conversation with a candid critique of contemporary dance reality shows, saying many now feel repetitive and indistinguishable from one another. In a recent interview, the performer reflected on how shows have evolved since the early days of televised dance competitions, expressing concern that originality and creative variety are increasingly being lost amid a sea of similar formats.

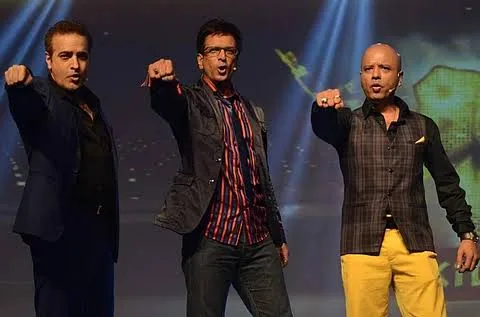

Jaaved, who rose to fame as a judge on iconic shows like Boogie Woogie, has been associated with dance television since its formative years in India. Boogie Woogie was among the first platforms to bring diverse dance talent into people’s living rooms, across genre, age and region. Its format was celebrated for showcasing a range of performers with distinct styles and personalities. Jaaved’s experience from those early days gives his observations particular weight, especially as shows today continue to dominate prime-time slots and social media discussions.

During his interview, Jaaved noted that in the current landscape, most dance reality shows follow very similar templates. From the way judges react to contestants to the types of challenges presented, he said there is a “sameness” that leaves little room for innovation. He said that while the energy and enthusiasm of dancers remain impressive, the packaging of the shows often relies on familiar structures rather than fresh creative risks or genuinely new formats.

Jaaved’s comments reflect a broader conversation in entertainment about how content evolves over time. When Boogie Woogie was at its peak, dance competitions on television were rare and groundbreaking for their inclusiveness and novelty. Contestants from all walks of life — children, adults, amateurs and professionals — competed and won applause simply for expressing themselves through movement. The show’s open-ended spirit helped popularise dance as a form of mainstream entertainment.

In contrast, Jaaved said, many of today’s competitions are marked by elaborate production values, heavily choreographed group performances and dramatic narratives designed to hook viewers. While these elements contribute to heightened entertainment value, they may also narrow the creative space in which dance can flourish. Judges, too, are often expected to serve as on-screen personalities with sharp critiques and sometimes dramatic interactions, potentially shifting focus from pure dance to television theatrics.

Several viewers and critics have responded to Jaaved’s remarks by agreeing that while talent remains abundant, the format fatigue is real. Some fans recalled the excitement and freshness of earlier shows, where every performance felt unpredictable and unique. Others said that the current format saturation reflected broader trends in reality television, where successful templates are replicated rapidly in hopes of maintaining audience attention.

Proponents of modern shows, however, have pointed out that the evolution of dance reality television also mirrors changes in audience expectations and media consumption. With streaming platforms and global competitions influencing local productions, the demand for high-energy performances and diverse dance genres has grown. In this view, similarity of format may be less about creative stagnation and more about meeting contemporary entertainment standards.

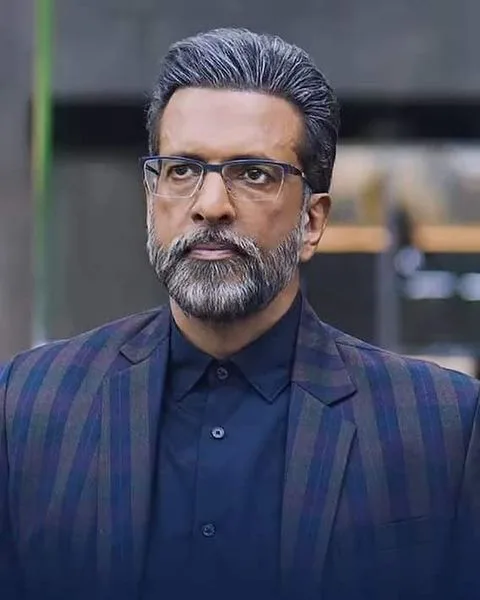

Despite differing opinions, Jaaved’s critique touches on an important conversation about the direction of televised dance programming. As someone who has seen the medium grow from its roots to its current expansive state, his reflections offer a moment to pause and consider whether innovation is being prioritised alongside commercial appeal.

Ultimately, dance reality shows remain a cultural force, giving many performers a chance to shine. The question raised by Jaaved’s observations may be less about whether the shows are good or bad, and more about how they can continue to push artistic boundaries while remaining relatable to viewers.