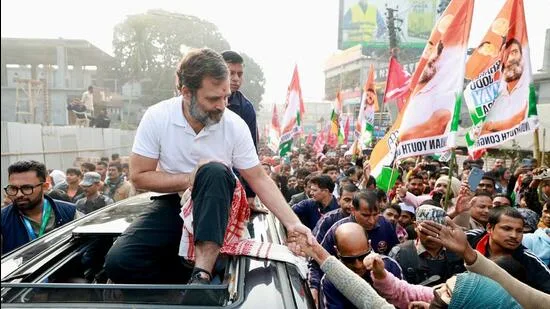

West Bengal is fast emerging as one of the most consequential theatres of Indian politics, not merely because of the contest between the Bharatiya Janata Party and the Trinamool Congress, but because of what it reveals about the Congress party’s shrinking relevance in states where it once mattered. Despite being the principal national Opposition and a key architect of the INDIA bloc, the Congress today is virtually out of the picture in Bengal’s electoral calculus. This marginalisation is not accidental, nor is it solely the product of organisational weakness. It is the outcome of a deeply conflicted relationship with the Trinamool Congress, compounded by the contradictions of alliance politics at the national level.

The irony is striking. While the Congress is the central pillar of the INDIA bloc nationally, it is one of the weakest players in West Bengal, a state that could shape the trajectory of Opposition politics in the years ahead. Bengal thus exposes a structural dilemma for the Congress: how to lead a national coalition while surrendering political space to its allies in key states, sometimes at the cost of its own survival.

From Principal Player to Residual Force

Historically, the Congress was a formidable force in Bengal. Even after the decline that followed the rise of the Left Front, the party retained pockets of influence and remained a serious stakeholder. That changed decisively after Mamata Banerjee broke away from the Congress in 1997 to form the Trinamool Congress. What followed was not merely a split but a gradual political replacement. The TMC did not coexist with the Congress; it steadily supplanted it.

The decisive rupture came in the post-2011 period, after Mamata Banerjee ended the Left’s 34-year rule. The Congress, which had allied with the TMC to defeat the Left, failed to reinvent itself once the TMC became the dominant pole of anti-Left and anti-BJP politics in the state. Electoral results since then have consistently shown the Congress reduced to single-digit vote shares, often eclipsed even by the Left in terms of organisational visibility.

Today, the Congress has no realistic pathway to power in Bengal. It lacks grassroots strength, credible leadership, and a narrative distinct from the TMC. This is not merely a matter of electoral arithmetic; it is a deeper crisis of political purpose.

A Relationship Split Between Delhi and Kolkata

At the heart of the Congress’s Bengal dilemma lies its paradoxical relationship with the Trinamool Congress. Nationally, the two parties are allies, bound together by the imperative of resisting the BJP. Regionally, they are adversaries, competing for the same ideological space of secular, welfare-oriented politics.

This duality creates strategic paralysis. In Delhi, the Congress depends on Mamata Banerjee’s parliamentary numbers and political legitimacy to project the INDIA bloc as a credible alternative to the BJP. In Kolkata, the same Congress is forced into an awkward posture: attacking the TMC risks weakening the Opposition’s national unity, while accommodating it accelerates the Congress’s own irrelevance in the state.

Unlike smaller regional parties, the Congress cannot afford to completely withdraw from Bengal. Doing so would symbolically concede a major state to an ally, undermining its claim of being a pan-Indian party. Yet, contesting seriously against the TMC would fracture the Opposition bloc and hand a narrative advantage to the BJP. The result is indecision masquerading as strategy.

Why Regional Parties Can Support TMC, But Congress Cannot

One of the most telling developments in recent months has been the open support extended to Mamata Banerjee by regional leaders from outside Bengal. Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav’s public endorsement of Banerjee, for instance, underlines a pragmatic logic: parties like the SP, DMK, or RJD have little or no stake in Bengal’s electoral battlefield. Supporting the TMC there costs them nothing and strengthens Opposition unity nationally.

For the Congress, the situation is fundamentally different. Bengal is not an “external” state; it is a historic bastion, however diminished. Every concession to the TMC in Bengal deepens the Congress’s organisational hollowing. Unlike other allies, the Congress competes directly with the TMC for minority votes, secular credentials, and Opposition leadership. Where regional parties see Mamata Banerjee as a useful bulwark against the BJP, the Congress sees her as both ally and usurper.

This asymmetry explains why alliance management that appears smooth at the national level becomes fraught on the ground in Bengal.

INDIA Bloc and the Cost of Leadership Without Leverage

The formation of the INDIA bloc was meant to reassert the Congress’s centrality in Opposition politics. Yet in states like Bengal, the bloc has paradoxically weakened the Congress further. By positioning itself as the unifying force, the Congress has had to accommodate powerful regional players without extracting reciprocal concessions at the state level.

In Bengal, this has translated into political invisibility. The Congress neither leads the Opposition narrative nor shapes electoral discourse. The BJP and the TMC define the contest, while the Congress is relegated to statements, press conferences, and symbolic alliances. Its criticism of the TMC remains muted, often inconsistent, and easily overshadowed.

This is not merely tactical weakness; it is structural. The Congress lacks the leverage to negotiate seat-sharing or ideological space in Bengal because it brings little electoral value to the table. Alliance politics, in this sense, has exposed rather than masked the party’s decline.

Minority Politics and a Narrowing Corridor

West Bengal’s political churn is also being shaped by evolving minority politics, a domain where the Congress once had a natural advantage. The TMC has successfully consolidated minority support through welfare schemes, representation, and a strong anti-BJP stance. The Congress, by contrast, struggles to articulate a compelling alternative.

This is particularly significant because minority consolidation leaves little room for a third player. In a polarised environment where the contest is framed as TMC versus BJP, the Congress is squeezed out, unable to mobilise either strategic voting or protest votes effectively. Unlike states where triangular contests persist, Bengal’s politics is increasingly bipolar, and such systems are unforgiving to marginal players.

The Left-Congress Contradiction

Adding to the complexity is the uneasy relationship between the Congress and the Left in Bengal. While the two have occasionally collaborated, their partnership remains fragile, marked by mutual suspicion and ideological divergence. For the Congress, aligning too closely with the Left risks further alienating centrist voters and reinforcing perceptions of decline. For the Left, the Congress is both competitor and liability.

This fractured Opposition space benefits the TMC, which positions itself as the sole viable alternative to the BJP. The Congress, caught between an assertive ally and an eroded base, finds itself without a clear strategic anchor.

What This Means for National Politics

The Congress’s marginalisation in Bengal has implications beyond the state. It raises uncomfortable questions about the sustainability of a national Opposition that depends disproportionately on regional parties for relevance. If the Congress cannot assert itself in states where it once mattered, its leadership of the INDIA bloc risks becoming symbolic rather than substantive.

At the same time, the party’s predicament also reflects a broader transformation in Indian politics, where regional leaders with strong state-level legitimacy increasingly shape national Opposition dynamics. Mamata Banerjee’s dominance in Bengal exemplifies this shift.

A Precarious Future

The Congress is not entirely absent in Bengal, but it is politically peripheral. It speaks without shaping outcomes, allies without influencing strategy, and contests without credible ambition. Unless it undertakes a long-term organisational rebuild independent of alliance compulsions, its role in Bengal will remain residual.

For now, the party appears trapped in a strategic bind of its own making: too weak to challenge the TMC, too important nationally to abandon the state, and too constrained by alliance politics to reinvent itself. Bengal, in this sense, is not just a state where the Congress is losing ground; it is a mirror reflecting the limits of the party’s current political model.

As Indian politics enters a decisive phase, West Bengal stands as a cautionary tale of how national dominance does not automatically translate into regional relevance, and how alliances, while necessary, can sometimes accelerate the very decline they are meant to prevent.