The Enforcement Directorate’s raids on the Indian Political Action Committee (I-PAC) in West Bengal have triggered a political storm that goes far beyond the confines of a money-laundering investigation. What might otherwise have remained a technical probe has instead snowballed into a volatile confrontation between the Mamata Banerjee-led Trinamool Congress and the BJP-ruled Centre, laying bare the deep mistrust between federal institutions and opposition-ruled states. In Bengal, where politics has always thrived on confrontation and symbolism, the I-PAC raids have become a lightning rod for anxieties about democratic space, electoral fairness and the use of central agencies as political weapons ahead of the 2026 Assembly elections.

The immediate trigger for the unrest was the ED’s decision to conduct searches at I-PAC’s Salt Lake office in Kolkata and at the residence of one of its senior functionaries, as part of an investigation linked to alleged money laundering in a coal smuggling case. From the agency’s standpoint, the action was routine and legally sanctioned, flowing from an existing probe. From the Trinamool Congress’s perspective, however, the raid crossed a red line. I-PAC, after all, is not merely a consultancy firm in Bengal’s current political imagination; it is perceived as an extension of Trinamool’s election machinery, deeply embedded in campaign strategy, data analytics and voter outreach. That perception, whether accurate or exaggerated, is central to understanding why the raid sparked such an immediate and fierce reaction.

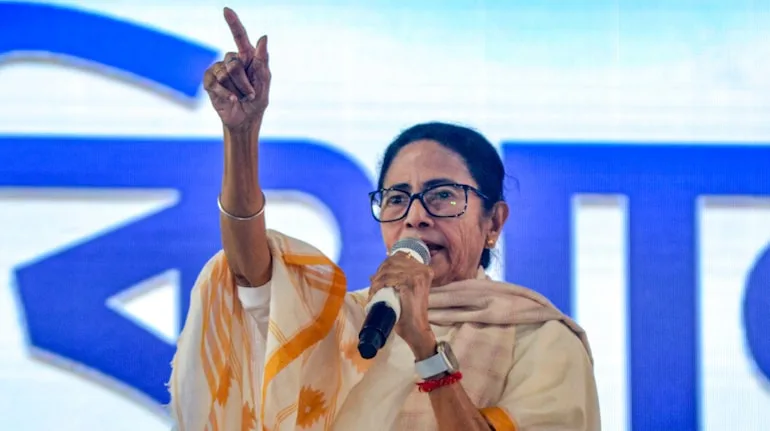

Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee’s dramatic intervention during the searches transformed the episode into a national controversy. Her personal appearance at the raid sites, her public allegations that ED officials were attempting to seize sensitive political and voter data, and her decision to remove documents and devices from the premises were unprecedented acts by a sitting chief minister. To her supporters, these actions symbolised defiance against what they see as an intrusive and partisan Centre. To her critics, they represented obstruction of justice and an alarming disregard for the rule of law. The ED’s subsequent move to approach the Calcutta High Court, accusing Mamata Banerjee of obstructing officials and interfering with evidence, hardened these opposing interpretations into irreconcilable narratives.

At the heart of the Trinamool Congress’s argument is the claim that the raid was not about financial irregularities but about political sabotage. Mamata Banerjee and her party have alleged that the ED sought access to confidential campaign strategies, internal communications and voter databases that could be misused to benefit the BJP in the run-up to the elections. This allegation taps into a broader opposition narrative that central agencies are being selectively deployed against non-BJP governments, especially at politically sensitive moments. In this telling, the I-PAC raid is not an isolated incident but part of a continuum that includes earlier ED, CBI and income tax actions against opposition leaders across India.

The BJP and the Centre have rejected these allegations outright, insisting that the ED is acting independently and within the framework of the law. They argue that no political party is above scrutiny and that Mamata Banerjee’s attempt to frame a criminal investigation as an assault on democracy is a calculated effort to shield potential wrongdoing. From this vantage point, the chief minister’s intervention during the raid is portrayed as evidence of desperation rather than victimhood, reinforcing the BJP’s long-standing charge that corruption and cronyism flourish under the Trinamool regime. The party has been quick to amplify the ED’s claim that its officers were obstructed, using it to question Mamata Banerjee’s commitment to constitutional norms.

The political temperature rose further as the confrontation spilled onto the streets. Trinamool Congress leaders and workers staged protests across Kolkata, framing the raid as an attack on Bengal’s autonomy and dignity. Mamata Banerjee herself addressed rallies, declaring that India could not afford BJP rule and warning of an erosion of democratic values if central agencies were allowed to operate unchecked. These protests were as much about mobilisation as messaging. By casting the ED action as an external assault, the Trinamool leadership sought to consolidate its support base and revive the familiar narrative of Bengal standing up to Delhi.

Simultaneously, the legal battle expanded. The ED’s petition before the Calcutta High Court and the Trinamool’s counter-claims alleging violation of privacy and illegal seizure of political data turned the judiciary into a critical arena of this confrontation. Court proceedings were marked by high drama, with heated exchanges between lawyers and adjournments amid disorder, mirroring the chaos outside the courtroom. The legal questions raised by the case are profound. They touch upon the extent of investigative agencies’ powers, the rights of political parties and consultancies to protect sensitive data, and the limits of executive intervention during law enforcement operations. How the courts navigate these questions will have implications far beyond Bengal.

The controversy has also brought political consultants like I-PAC into sharper public focus. Over the past decade, such firms have become influential actors in Indian elections, operating at the intersection of data, messaging and grassroots mobilisation. I-PAC’s assertion that it has worked with multiple parties across the political spectrum and that the raid sets an “unsettling precedent” underscores a growing unease within the political ecosystem. If consultancy firms are perceived as vulnerable to investigative overreach, it could alter how parties engage with professional strategists and how electoral data is managed in the future.

Adding another layer to the unfolding drama is the personal and political escalation between Mamata Banerjee and the BJP’s Bengal leadership. Leader of the Opposition Suvendu Adhikari’s decision to send a legal notice to the chief minister, threatening a defamation case over what he calls baseless corruption allegations, signals a sharpening of the rhetorical battle. This move reflects the BJP’s strategy of pushing back aggressively against Mamata’s claims, not only in the political arena but also through legal channels. It also highlights how individual rivalries are becoming intertwined with institutional conflicts, amplifying the sense of political instability.

In the broader national context, the I-PAC raids have reinforced opposition concerns about the shrinking space for dissent. Leaders from other non-BJP parties have rallied around Mamata Banerjee, seeing in her confrontation with the ED a test case for federal resistance. For them, the issue is not whether corruption should be investigated but whether investigative agencies are being deployed selectively and strategically to weaken political opponents. This perception, whether fully grounded or not, has gained traction over recent years and now finds renewed expression in the Bengal crisis.

For the BJP, however, the episode is an opportunity to reframe the political discourse in the state. After failing to unseat Mamata Banerjee in the 2021 Assembly elections, the party has struggled to sustain momentum in Bengal. By foregrounding allegations of corruption and highlighting Mamata’s alleged obstruction of an ED probe, the BJP hopes to shift the conversation away from identity and welfare politics to questions of governance and accountability. In this sense, the Centre’s firm backing of the ED is as much a political calculation as a legal stance.

The Bengal electorate now finds itself caught between these competing narratives. To Trinamool supporters, the sight of a chief minister confronting central agencies reinforces Mamata Banerjee’s image as a street-fighter willing to challenge Delhi. To BJP sympathisers, the same images confirm suspicions of a leader with something to hide. For undecided voters, the constant spectacle of raids, protests and court battles may deepen cynicism about all sides, raising questions about whether governance has taken a back seat to perpetual confrontation.

As the state edges closer to the 2026 elections, the political consequences of the I-PAC raids are likely to intensify. The legal outcomes will matter, but so will the perceptions shaped in the public mind. If the courts appear to endorse the ED’s actions, it could embolden the Centre and strengthen the BJP’s corruption narrative. If, on the other hand, the judiciary finds fault with the agency’s conduct or upholds claims of overreach, it could validate opposition fears and bolster Mamata Banerjee’s defiant stance.

Ultimately, the diatribe surrounding the ED raids on I-PAC reflects a deeper crisis of trust in India’s political system. It exposes the fragile balance between enforcement and politics, between federal authority and state autonomy, and between democratic accountability and political expediency. In West Bengal, a state long accustomed to political turbulence, this episode has once again turned governance into a battleground of narratives. Whether it will translate into electoral advantage for one side or further polarise an already divided polity remains an open question. What is clear is that the I-PAC raids have ceased to be merely about an investigation; they have become a symbol of the high-stakes struggle for power, legitimacy and narrative control in contemporary Indian politics.