When the EC’s June 24, 2025 draft order for the nationwide SIR first surfaced, it did more than announce a clean-up of electoral rolls. According to internal records reviewed by The Indian Express, the draft explicitly invoked the Citizenship Act, 1955 (as amended in 2003) to justify the exercise, arguing that no intensive national revision had been conducted since the amendment, and therefore, the time had come to revisit the rolls to ensure that only “citizens as per the Constitution” remain registered voters.

In that draft order, one of the three Election Commissioners, Sukhbir Singh Sandhu, inserted a cautionary note: “Care should be taken that genuine voters/citizens, particularly old, sick, PwD (persons with disabilities), poor and other vulnerable groups do not feel harassed and are facilitated.”

Yet when the final order was formally issued that very evening, references to the Citizenship Act and the logic based on citizenship reportedly vanished. The final order retained only a reference to constitutional voter rights under Article 326, and a truncated clause about citizenship that ended abruptly after a semicolon.

This deletion, along with the last-minute approval of the order via WhatsApp, suggests the EC was acutely aware of the political and social volatility the draft reasoning could trigger. But the cautionary note from Sandhu, and the original invocation of citizenship law, remain on record, making the final order’s vagueness look like a strategic move to avoid backlash, while the underlying logic of SIR continues to resemble a citizenship verification exercise.

A Rush That Echoes Demonetisation: More Haste, More Hassle, Less Transparency

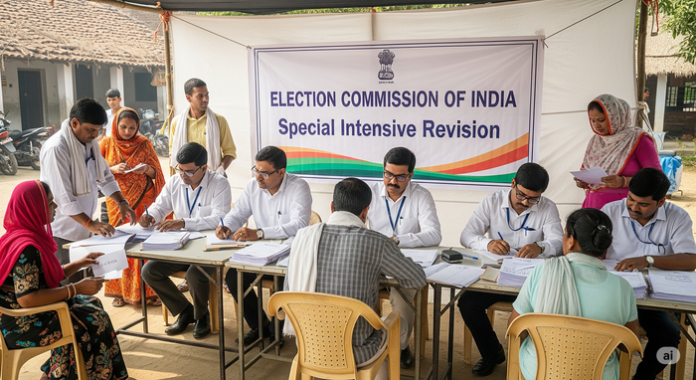

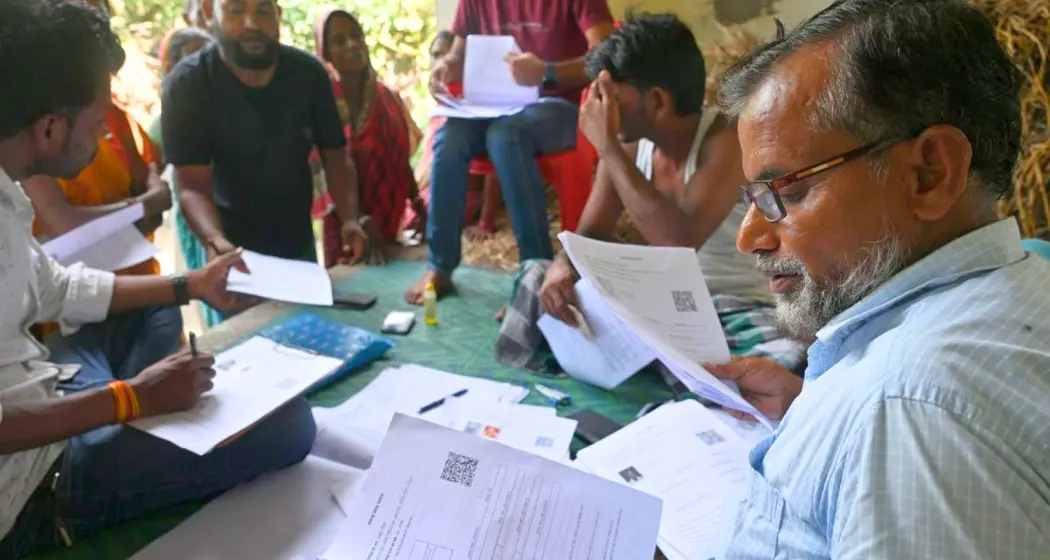

The SIR is not just a routine update: by the EC’s own admission, it is an “intensive revision,” meaning every listed elector, even those holding valid voter IDs, must fill fresh enumeration forms, and many will have to submit documentary proof of identity, birth and residence. Unlike summary or periodic revisions over the years, this kind of top-to-bottom overhaul had not been done for decades.

The early phase of the drive, commissioned in Bihar, led to immediate chaos on the ground. Voters scrambled to gather paperwork, elderly and poor citizens protested that they lacked the required documents, and local offices were overwhelmed. Reports of confusion, delays and even mental distress among vulnerable populations surfaced rapidly. What was pitched as a “clean-up” turned into a massive bureaucratic clearance exercise, not unlike the 2016 demonetisation, which imposed sudden administrative burden on citizens while promising long-term public benefit.

The EC seemed to recognise this risk from the outset. That is likely why the draft order carried Sandhu’s warning, and the final order quietly dropped citizenship-based language, even though the spirit of the exercise remained focused on verifying voter eligibility through documentation.

Critics have argued that this underlines the deeper aim of SIR: not merely updating electoral rolls, but purging them of individuals deemed “suspect,” undocumented or unable to prove lineage, criteria strikingly similar to what members of that other controversial exercise, the National Register of Citizens (NRC), are asked to fulfill.

Institutions vs. Democracy: Constitutional Powers Do Not Mask Political Risk

Proponents of the SIR argue that the EC is constitutionally empowered under Article 324 to manage electoral rolls, and that Article 326 confers the right to vote only on adult Indian citizens.

However, critics, including opposition parties and civil society, maintain that citizenship verification is squarely under the domain of the Ministry of Home Affairs and governed by the Citizenship Act, not the EC. By design or by default, SIR straddles this institutional boundary, effectively functioning as a backdoor NRC without explicit safeguards.

Legal petitions challenging the SIR process in states like West Bengal and Tamil Nadu have argued that such a widespread citizenship-linked verification by the EC undermines electoral and constitutional rights, especially for poor, migrant, elderly and vulnerable people.

The EC has defended itself, telling the Supreme Court that it has “complete discretion” over when and how to revise electoral rolls and that performing SIR does not require any external agency’s approval. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court has asked petitioners to specify why they are so “apprehensive,” even as legal challenges continue.

The Final Rolls, the Real Fallout: Exclusion, Distrust, Disenchantment

In Bihar, where the first phase of SIR concluded on September 30, 2025, the final electoral roll published by the EC reportedly showed a shrinkage of about 6% in the electorate.

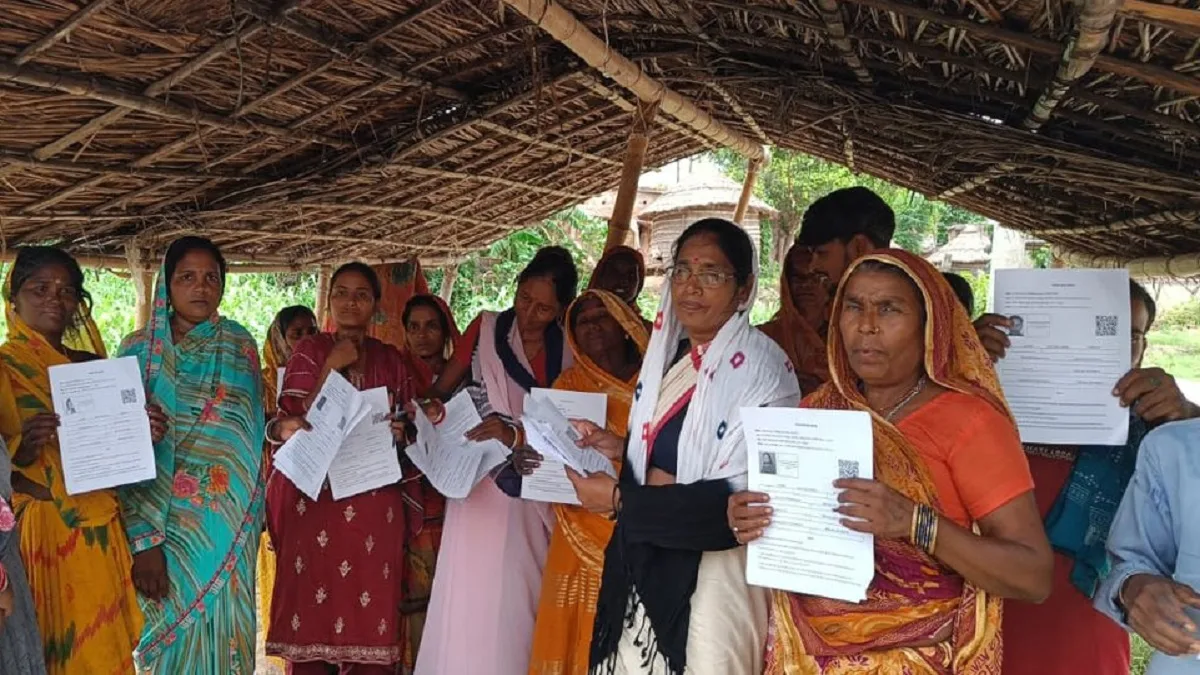

Even as the EC declared that the exercise was successful and that no large-scale deletion of genuine voters had been reported, the psychological and sociopolitical impact has already begun to surface. In states like West Bengal and Assam, where large migrant populations and socio-economically vulnerable groups reside, the SIR has sparked fear, of exclusion, of loss of political identity, of being rendered stateless in practical terms.

For many citizens, especially poor migrants, labourers, elderly or homeless individuals, the burden of producing birth certificates, parental records or address proofs is real and immediate. For them, SIR smacks less of democratic reform and more of existential jeopardy. The fact that the EC quietly stripped explicit citizenship-test language from its final order does little to reassure those now scrambling to prove their lineage or birthright before bureaucrats and BLOs.

SIR as “Clean-up,” but Risk of Clean-out

Viewed in isolation, the SIR could be defended as a noble attempt to purge duplicate, fake or defunct voter entries, and to ensure accurate and up-to-date electoral rolls. Yet the origins of the exercise, the citizenship-linked draft order, the constitutional invocation of Article 324 and 326, the sudden urgency, reveal a far more loaded agenda.

By structurally mirroring an NRC-style citizenship verification, SIR threatens constitutional values of equality, universal adult franchise and non-discrimination. It carries the risk of disenfranchising millions who are unable to jump through documentary hoops, not due to fraud, but because of systemic disadvantage.

If not countered by robust oversight, transparent documentation, legal safeguards and political will, SIR may end up less like a democratic renewal drive and more like a stealth exclusion mechanism, leaving behind a legacy not of inclusion, but of fear and fractured civic identity.