West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has once again taken centre stage in a high-stakes political and constitutional battle by moving the Supreme Court against the Election Commission of India (ECI) and its ongoing Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls. What might, at first glance, appear to be a routine legal challenge has become a flashpoint in Indian politics, one with implications that extend far beyond state borders, resonating with broader questions of electoral fairness, federal balance, and political survival in an era of intensely polarised elections.

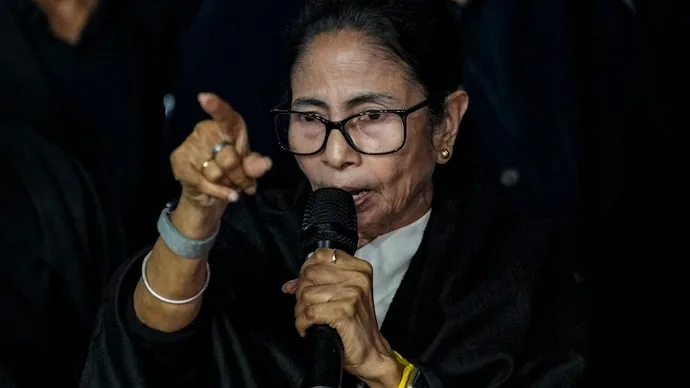

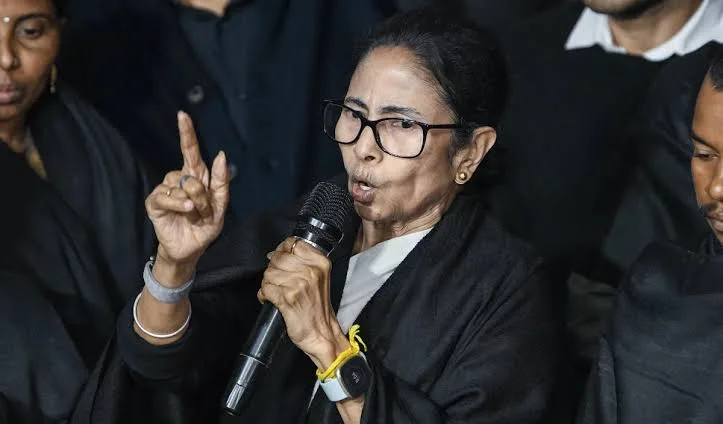

Banerjee’s decision to personally spearhead her legal fight, appearing before the Supreme Court and publicly challenging the ECI’s actions, underscores both the urgency she attaches to the matter and the broader political theatre it now occupies. For observers, the unfolding confrontation raises vital questions: Is this move a shrewd tactical escalation by a seasoned regional leader defending her political base? Or is it an act of desperation by a chief minister whose dominion is under unprecedented pressure from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)? To understand the stakes, one must look at the context, the substance of the dispute, and its wider reverberations.

What Is the SIR Row About?

The controversy centres on the Special Intensive Revision of electoral rolls (SIR), a process implemented by the ECI in several states, including West Bengal, to update and clean voter lists. While the commission characterises SIR as a routine but focused revision exercise, the Opposition and regional parties, led most vocally by Banerjee, have decried it as a politically motivated effort to disenfranchise voters, especially among poor, marginalised and rural populations. They argue that the process targets groups that traditionally support non-BJP parties, a claim that the ECI has categorically denied.

In early February 2026, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Banerjee’s petition challenging the legality and manner of the SIR exercise. As reported, the bench considered arguments on whether the ECI had overstepped its mandate and whether the SIR could compromise the fundamental right to vote. Banerjee’s legal team argued that recent electoral roll revisions lacked transparency, disproportionately affected certain demographic groups, and were conducted without adequate safeguards to prevent wrongful deletions.

For Mamata Banerjee, this legal battle is not only about procedure,it is about the integrity of the electoral process itself. She has framed her plea in constitutional terms, arguing that aggressive roll revision without clear and fair remediation mechanisms is tantamount to disenfranchisement. But beyond the constitutional argument lies fierce political calculation.

The Political Context: Bengal and Beyond

West Bengal is a key battleground in India’s 2026 political cycle. The state’s electorate has repeatedly rejected the BJP’s attempts to make inroads; yet the BJP has steadily increased its footprint in recent elections, reducing the margin and intensity of the TMC’s dominance. Amid this backdrop, the SIR controversy has become a lightning rod for voter anxieties about electoral fairness, representation and democratic agency.

Banerjee’s challenge stokes these anxieties in a deliberate way: by presenting herself as the defender of the voter, not merely the defender of her party or office. Her speeches and statements often cite personal stories of voters who risked being dropped from rolls, emphasising the existential anxiety of losing a constitutional right. As she said after meeting the Chief Election Commissioner (CEC), the SIR process “harasses the weak and the downtrodden”, and she directly accused the ECI of refusing to provide “data and clarity” on roll deletions.

At a protest rally, she even turned to poetry to articulate her resistance, reflecting both her rhetorical style and the cultural register she uses to connect with supporters. For Banerjee, the optics are as important as the legal arguments. By depicting the fight as one for democracy itself, she taps into deep currents of political resentment against perceived centralisation and administrative overreach.

Why the Supreme Court Filing Matters

Banerjee’s decision to take the fight to the Supreme Court, and to make her own appearances and statements, is remarkable for several reasons.

First, it signals a break from purely street-level or legislative opposition. Legal battles bring issues into a different terrain where evidence, procedure, and judicial norms constrain political rhetoric. For Banerjee, the Supreme Court is not just a forum to argue law; it is a platform to nationalise the debate and legitimise her claims of systemic bias.

Second, it underscores the erosion of faith in institutional resolution through political means. Banerjee’s remarks, that the ECI was “trying to save face” rather than address genuine concerns, reflect a broader scepticism about the neutrality of institutions perceived to be aligned with the ruling party. This stance has traction among a significant constituency of voters who view the election machinery with distrust.

Third, her personal involvement in the Supreme Court signals both confidence and necessity. Unlike many political leaders who rely on legal teams, Banerjee has chosen to be physically present, underscoring the political weight she attaches to the case.

Impact on Regional Politics

In West Bengal, Banerjee’s legal offensive reinforces her image as a fighter, a leader who does not shy away from direct confrontation with powerful institutions. This approach resonates with her long history of resisting both political rivals and bureaucratic inertia. However, the strategy also carries risks.

The most immediate impact is on the voter psyche. In a state where political mobilisation often centres on both identity and grievance, Banerjee’s portrayal of the SIR process as disenfranchisement can sharpen anti-Centre sentiment, galvanising support among constituencies that feel vulnerable to administrative exclusion.

It also deepens the rift between the Congress, Left parties and the TMC in West Bengal. While both Opposition groups have criticised the SIR exercise, the Congress has been less visible in leading the charge, leaving Banerjee and the TMC to dominate the narrative. This has implications for coalition politics and Opposition realignment. If the Congress cannot assert itself on a contentious issue that directly affects the electorate, its own relevance in Bengal weakens further.

National Ramifications

Nationally, the case complicates the electoral logic for the BJP and the ECI. The ECI, constitutionally independent but politically sensitive, has defended the SIR process as within its powers and not targeted at any party. But by being pulled into the Supreme Court, the ECI’s actions are now subject to judicial scrutiny and the political fallout from that scrutiny.

For the BJP, the rapid transformation of SIR into a politically charged national issue is both a liability and an opportunity. On one hand, the BJP can argue that every government, including those led by TMC or Congress in their states, must maintain accurate rolls. On the other hand, the optics of voters being removed from rolls in poll-bound states, whether justified or not, feed into narratives of disenfranchisement that cut against the BJP’s claim of democratic inclusiveness.

The Supreme Court hearing also elevates the SIR issue beyond state-specific grievance to a national conversation on election management and institutional accountability. If the court finds merit in Banerjee’s case, it could curtail the ECI’s discretion on how intensely to pursue roll clean-ups in future elections. If the court upholds the Commission’s actions, it may further embolden the ECI’s approach in other states, but at the cost of contributing to narratives of institutional bias.

Is Mamata on the Right Track?

Evaluating whether Banerjee is on the “right track” requires separating legal merit from political impact.

From a legal standpoint, her challenge focuses on due process, transparency, and constitutional safeguards. These are legitimate questions and the Supreme Court, by hearing the matter, signals that there is at least arguable substance to her claims. Democracies flourish when electoral processes are subject to open judicial scrutiny, especially when claims of systematic exclusion are made.

Politically, the strategy aligns with Banerjee’s core strengths. She is at her most potent when combining grassroots mobilisation, emotive rhetoric, and institutional challenge. By framing the SIR issue as a fight for democratic rights, she expands her appeal beyond partisan followers to voters who may be uneasy about complex administrative processes.

Yet there are risks. The strategy can alienate voters who prioritise effective governance over legal confrontation. It may deepen polarisation without addressing the substantive concerns that voters have, such as employment, prices, public safety, and development. Moreover, positioning herself as the chief challenger to the ECI could have unintended consequences if it is seen as undermining an independent institution rather than reforming it.

Finally, the nationalisation of the issue can cut both ways. It consolidates Banerjee’s profile within the INDIA bloc and among Opposition supporters, but it also intensifies scrutiny from national media and critics who may portray her actions as obstructionist or publicity-driven.

The Stakes Ahead

As West Bengal hurtles towards its next Assembly election, the SIR controversy and the Supreme Court hearing have become defining elements of the state’s political discourse. For Mamata Banerjee, winning the legal battle would reinforce her narrative of resistance and protect the electoral prospects of her party’s base. Losing, however, could weaken her claim to be the guardian of democratic rights at precisely the moment when political momentum matters most.

Whether this is a “last chance” or a robust tactical escalation depends on one’s perspective. For Banerjee, it is neither mere theatrics nor simple legal strategy: it is a high-stakes bid to redefine the terms of electoral competition in her state and, by extension, challenge the narrative of central dominance. For Indian democracy, it is a reminder that questions about electoral rolls, voter inclusion, and institutional impartiality remain central to the health of the republic.

In the end, Mamata’s Supreme Court gambit may be as consequential for constitutional jurisprudence as it is for West Bengal’s political landscape. It is a battle that extends beyond party lines, touching the core democratic values of fairness and participation. How it unfolds will matter not just for one party or state, but for the broader contest over who shapes India’s democratic future.