In a quiet yet compelling post-watch reflection, actress Sobhita Dhulipala revealed how the Tamil coming-of-age drama Bad Girl moved her—to the point of tearing up—and described the experience as one of being genuinely “seen”. Her words cut through the usual promo chatter and point to something deeper happening in how audiences and performers engage with cinematic narratives.

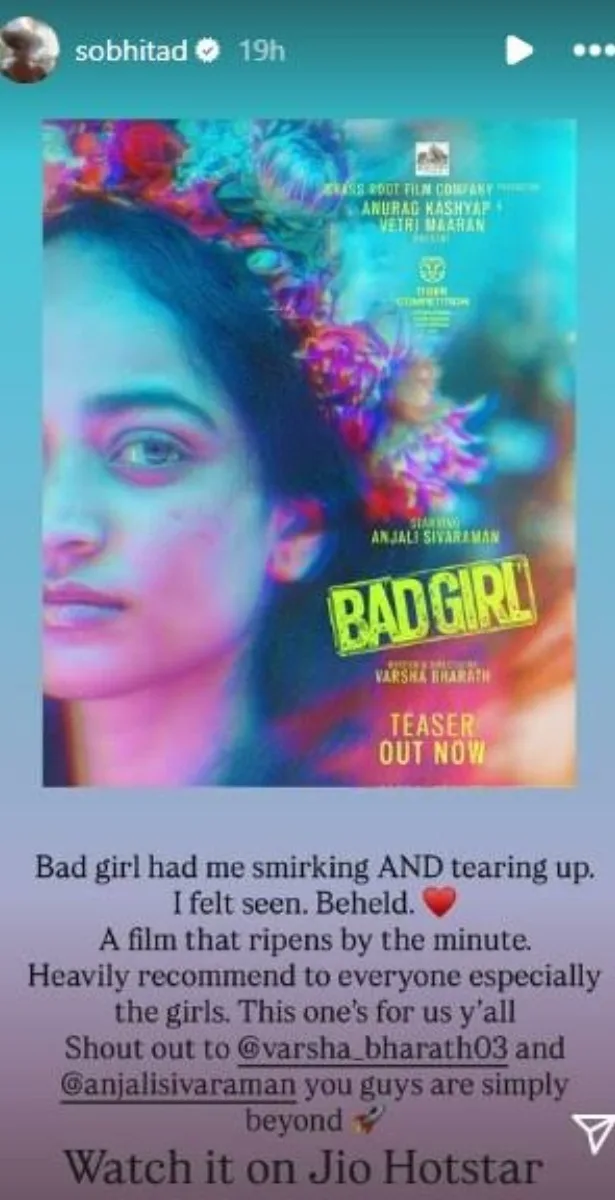

On 11 November 2025, Sobhita took to her Instagram Stories, sharing the film poster of Bad Girl and writing, “Bad Girl had me smirking AND tearing up. I feel seen. Beheld. (heart emoji) A film that ripens by the minute. Heavily recommend to everyone, especially the girls. This one’s for us, y’all. Shout out to @varsha.bharath3 and @anjalisivaraman you guys are simply beyond (confetti emoji). Watch it on Jio Hotstar.”

Bad Girl, the debut directorial by Varsha Bharath and starring Anjali Sivaraman, had already made headlines before its release—tackling female adolescence and identity with a blunt edge, and stirring controversy for its bold depiction of a Brahmin girl’s personal life. In choosing her words, Sobhita Dhulipala emphasised the film’s resonance: it wasn’t only her viewing experience; it felt like someone finally articulated a part of her.

Why Sobhita Dhulipala’s reaction matters

Sobhita Dhulipala’s reaction matters for several reasons. First, it flips the promotional script. Typically actors share measured blurbs. Here, her admission of vulnerability—“I teared up and felt seen”—speaks to a lived identification with the film’s themes. It opens a window into how a cinema that centres female experience can break through habitual male-centred narratives.

Second, the endorsement taps into female viewership in a deliberate way. Sobhita explicitly called the film “for us, y’all” and urged “especially the girls” to watch it. Her vantage as an outsider-actor in the Hindi/South crossover space and her willingness to speak candidly position her as a bridge between personal feeling and public call-out. That amplifies the film’s reach beyond pure fandom.

Third, when a known performer sees herself in a character, it signals cultural alignment. Sobhita is better known for her roles in Made in Heaven and OMG 2 than for overtly rebellious cinema. Her declaration signals a shift: female actors no longer only play roles—they recognise and react to them out loud. That commentary becomes part of the film’s narrative life.

For the film’s makers and cast, the upward ripple effect is clear. Sobhita Dhulipala’s praise gives Bad Girl a premium seal of approval outside its own promotional channels. The endorsement built around emotional authenticity provides a layer of credibility—especially since the film had previously faced backlash.

This also intersects with a larger cultural moment. In recent years, viewers—including women—have sought cinema that touches identity, selfhood, vulnerability and societal expectation. Films that articulate “feeling seen” emphasise listening to female voices. Sobhita’s reaction affirms this appetite.

Also Read: Shehnaaz Gill Peeks Into Salman Khan’s ‘Desi’ Side; Talks About Farmhouse Party

The moment invites us to ask: what does “felt seen” really mean in this context? It suggests the film’s narrative allowed a performer to recognise her reflection—not just metaphorically, but visual, emotional, existential. It means the lens found her rather than her seeking it. That sensation bridges the gap between performer and viewer.

In practice, this is less about the film’s box-office performance and more about its cultural imprint. Whether or not Bad Girl sets records, its ability to prompt responses from actors like Sobhita underscores its relevance. It demonstrates that stories about young women, their choices, struggles and real-life echoes still matter.

At the same time, for Sobhita’s trajectory, the moment is revealing. She is stepping into commentary space—not just ‘what she acts in’ but into what she watches, feels and advocates. That turn—from actress to commenter—suggests her evolution and deepening connection to stories of substance.

Ultimately, the exchange between film and actor, viewer and character, is part of the story’s afterlife. Sobhita’s “I felt seen” is more than praise—it is a public alignment of identity, emotion and narrative. It invites audiences to watch the film not just as entertainment but as mirror.

And in an industry still dominated by blockbuster spectacle, these quietly viral moments can reshape reading of cinema. Not just what we watch, but how the film watches us—how we see ourselves in it.